ADHD and Behaviour.

The narrative around ADHD in the classroom has been dominated by a focus on "disruptive behavior". When a student struggles with organization, focus, or emotional regulation, it is often viewed considered to be ‘bad behaviour.’

However, if we view ADHD as a neurodevelopmental condition , we understand that this ‘bad behaviour’ is often direct manifestations of challenges with Executive Functions. The school environment, with its demands for sustained attention and rigid structures. It ultimately is not an environment designed for neurodivergent students.

This post will guide you through recognizing the roots of these behaviors and implementing effective, respectful strategies—starting with a crucial shift in perspective.

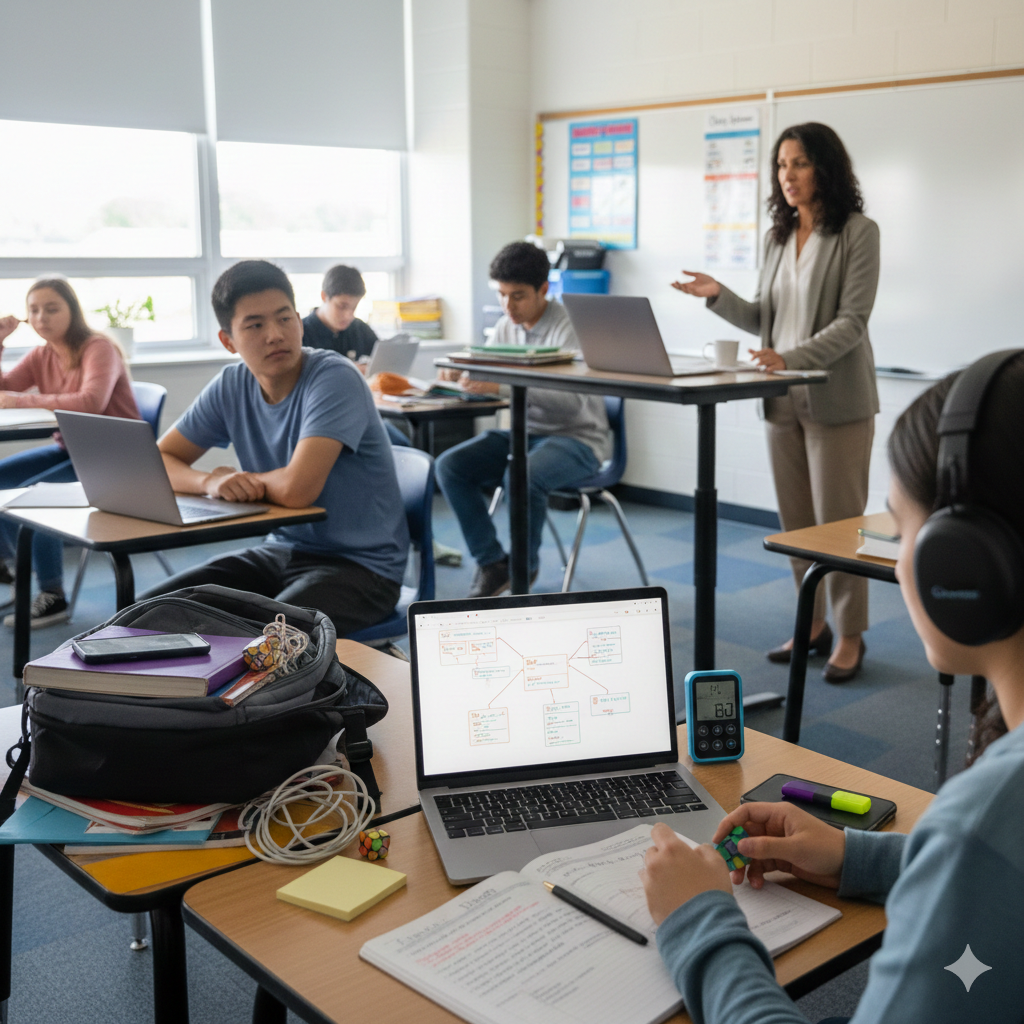

Navigating Misunderstandings: This image captures a common point of friction during the transition to Post Primary school. What looks like disinterest or defiance to a teacher is often a sign of overwhelm or sensory overload in a student with ADHD. Our session explores how to interpret these signals correctly and de-escalate classroom tension.

Understanding The Challenges Behind ‘Bad Behaviour.’

At the heart of ADHD difficulties are challenges with the eight core Executive Functions. These are the cognitive skills that regulate our thoughts, behaviors, and actions

Task Initiation - struggling to start a task.

Working Memory - forgetting instructions or information.

Organisation - struggling to structure information or manage materials.

Impulse Control - interrupting, making "risky" choices.

Emotional Regulation - easily getting angry or upset, being confrontational when challenged.

Flexibility - struggling with last-minute changes, fixed mindset.

Planning - struggling to structure a task or manage deadlines.

Self-Monitoring - struggling to self-soothe or self-regulate.

Because these functions are impaired, seemingly simple tasks—like packing a bag or moving between lessons (transition time)—can become overwhelming very quickly.

The Reality of Executive Dysfunction: As students move from Primary to Post Primary, the demand for organizational skills skyrockets. This image represents the internal state of a student facing "paralysis by analysis." We will discuss practical strategies to help students manage their physical space and mental load to prevent academic burnout.

Communication: Mindful Language and RSD.

Language has a measurable impact. Children with ADHD may receive up to 20,000 more negative messages than their neurotypical peers by age. This volume of criticism contributes to high anxiety rates 31and a common experience called Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD)—a hypersensitivity to perceived criticism or rejection.

To combat this:

Avoid labeling words like lazy, distracted, forgetful, or messy.

Use the 1:5 Rule: Aim for a ratio of five positive comments for every negative one..

Focus on Solutions, Not Faults: Reframe your comments to explore obstacles and offer assistance.

Low-Effort, High-Impact Strategies.

Effective ADHD strategies focus on modifying the environment and building scaffolds to support the challenged executive

Classroom Environment & Sensory Support.

Routine and Consistency: Establish clear routines, rules, and post a visual daily schedule. Consistency is essential as it removes the need for constant thinking about what comes next.

Strategic Seating: Collaborate with the student on seating. What you consider distracting (like the window) may not be for them, and vice versa. Allow for flexible seating (e.g., a wobble cushion or standing desk).

Sensory Aids: An ADHD brain needs the right level of constant stimulation. Use fidget toys, Loop Earplugs to limit external noise, or use dimmable lights/lamps instead of fluorescent lights which can cause sensory overload.

Academic Scaffolds

Chunking and Clarity: Keep instructions brief and clear. Get the student's attention first, and ask them to repeat instructions. Break long assignments into smaller, manageable stages with clear goals.

Task Initiation: Provide a "Brain Dump" (scrap paper for extra thoughts) to help organize and focus. Use visual timers (like a Pomodoro Timer) to help them start and maintain a flow state.

Visual Supports: Provide graphic organizers, mind maps, and examples of what the work should look like. You can even use AI to generate a step-by-step guide for complex tasks like an essay.

By focusing on these practical strategies and embracing a strength-based mindset, you can effectively manage challenging behaviors and create a supportive learning environment where every student, including those with ADHD, can truly thrive.